The United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends that clinicians screen adults for unhealthy alcohol use in primary care settings, provide brief counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use, and refer to alcohol use disorder (AUD) treatment as warranted – a process often referred to as Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment, or SBIRT.

National surveillance data covering 2015–2019 found that the rate of AUD among U.S. adults was 8 percent. Over 80 percent of those surveyed who had AUD reported using health care in the past 12 months and 70 percent reported having been screened for unhealthy alcohol use. However, only 5 percent of individuals with AUD were referred to treatment and only 6 percent received treatment. Although unhealthy alcohol screening is increasingly being used in primary care and other medical settings, referral and treatment initiation are severely lacking.

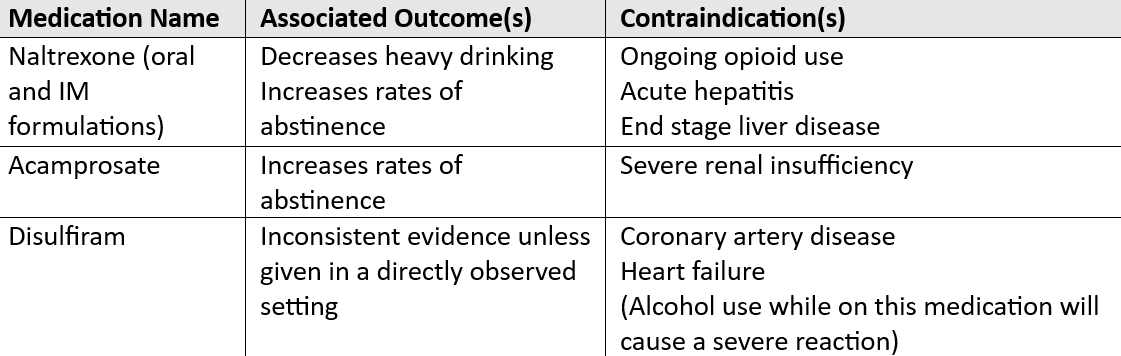

In addition to referring to outside counseling or peer support services, primary care clinicians can support patients in reducing or abstaining from alcohol use by prescribing medications for AUD. Much like medications for opioid use disorder, the goals of using pharmacotherapy for AUD include reducing unhealthy alcohol use, reducing alcohol-associated morbidity and mortality, and improving overall wellness. There are three FDA-approved medications for the treatment of AUD (naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram, discussed below), and multiple other medications have been studied for off-label use.

What does this look like in a primary care setting?

Screening and Brief Intervention

- The medical assistant asks a validated alcohol screening question at intake. Many primary care offices use the single-item alcohol screening question: “If you drink alcoholic beverages, how many times in the past year have you had 5 (men)/4 (women) or more drinks per day?”)

- If the patient answers that they have consumed that much one or more times in the past year , the next step is to complete a more comprehensive validated screening, like the 10-question US-AUDIT (see page 35).

- Scores of 0–7 require no intervention.

- Scores of 8–15 suggest drinking above guidelines, which merits a brief intervention. Brief interventions may be offered by behavioral health clinicians, if available in the primary care setting, or by the medical clinician.

- Scores of 16 or higher suggest the need for an AUD assessment and possible referral

Assessment and Diagnosis of Alcohol Use Disorder

A behavioral health or medical clinician uses the DSM 5 criteria to diagnose AUD.

- 2–3 symptoms indicate mild AUD.

- 4–5 symptoms indicate moderate AUD.

- 6+ symptoms indicate severe AUD.

Assessment for Risk of Severe or Complicated Withdrawal

The medical clinician will assess for risk of severe or complicated withdrawal, which can be life threatening in rare cases.

- Patients with history of complicated withdrawal may need medically monitored “detox” prior to considering long-term treatment planning. Guidance on risk assessment can be found in the ASAM Alcohol Withdrawal Management Guidelines.

- Patients with more mild withdrawal symptoms can be appropriately managed in an outpatient setting. Guidance on outpatient alcohol withdrawal management can be found in Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome: Outpatient Management.

Treatment Planning and Medication Initiation

After completion of any necessary alcohol withdrawal management, patients meeting the diagnostic criteria for AUD discuss counseling and pharmacotherapy options with the medical clinician.

The three FDA-approved medications for the treatment of AUD are:

Because disulfiram does not have evidence for improved outcomes outside of settings with directly observed medication dosing, it is generally not recommended for use in traditional primary care/outpatient settings.

Naltrexone and acamprosate are considered first-line pharmacotherapies for the treatment of alcohol use disorder. Neither are controlled substances, so they can be prescribed by any clinician with prescribing authority. Additional information on medication mechanism of action, dosing, and side effects can be found in Medications for Alcohol Use Disorder, which also includes an overview of medications that have been studied for off-label use for the treatment of AUD.

Follow-Up

Follow-up frequency often depends on clinician availability and whether the patient is engaging in other alcohol counseling or treatment programming.

- When possible and based on clinician and patient schedules, frequently following up during the first weeks and months of treatment (for example, every 1–2 weeks) can be helpful to discuss medication adherence and side effects, as well as the medication’s impact on alcohol cravings and consumption.

- As patients stabilize, the frequency of visits decreases.

- If a patient does not see improvement, typically the clinician would work with the patient to adjust pharmacotherapy and discuss increased intensity of behavioral health programming. For example, if the patient is not engaging in addiction counseling, the discussion would examine whether that is the next thing to incorporate. Or, if the patient is already in outpatient programming, the discussions might consider a higher level of care, such as intensive outpatient or residential care.

In Conclusion

Primary care practices are increasingly screening for unhealthy alcohol use, but referral to treatment and pharmacotherapy treatment initiation in primary care remains low. Offering these services can reduce unhealthy alcohol consumption and improve patient health and well-being. Practices that are already offering medications for opioid use disorder are well-positioned to offer medications for AUD as well.

Additional Resources:

Patient handout on the treatments for Alcohol Use Disorder